It takes a lot to stand out in the horror genre today. Great films are coming out left and right, mining the turmoil of our time for a renessance of intelligent chills. Still, there’s plenty of timeless horrors, which is where Went Up The Hill departs from many of its contemporaries. It’s concerned with pains that’ve been around for as long as humans have, ones that should be familiar to all but are too often tucked out of view.

The film opens with a young man, Jack (Dacre Montgomery), tentatively going up the hill. He’s in a gloomy, misty part of New Zealand, one he is unfamiliar with, and he enters an equally unfamiliar home. Inside are mourners, close friends and family of a deceased woman gathered to remember and say goodbye. The body is laid out in an imposing room. The whole house is imposing, really, a modern building of cold walls and crisp lines.

Jack knows no one here, including the dead woman, but he should have. The woman was his mother, who he hasn’t seen since he was removed from her home as a small child. With little memory and many questions, he’s come to find whatever answers are still available. His existence was so little known that the woman’s wife, Jill (Vicky Krieps), was unaware of him. Still, she lets him stay in her home, tentatively sharing in her outpouring of grief.

Thus sets up a two-hander, with Montgomery and Krieps holding together a film where their characters try to extricate themselves from a woman whose hold is so strong not even death breaks it. And that’s not metaphorical. She returns every time they go to sleep, possessing their bodies in turn to wrap up their business.

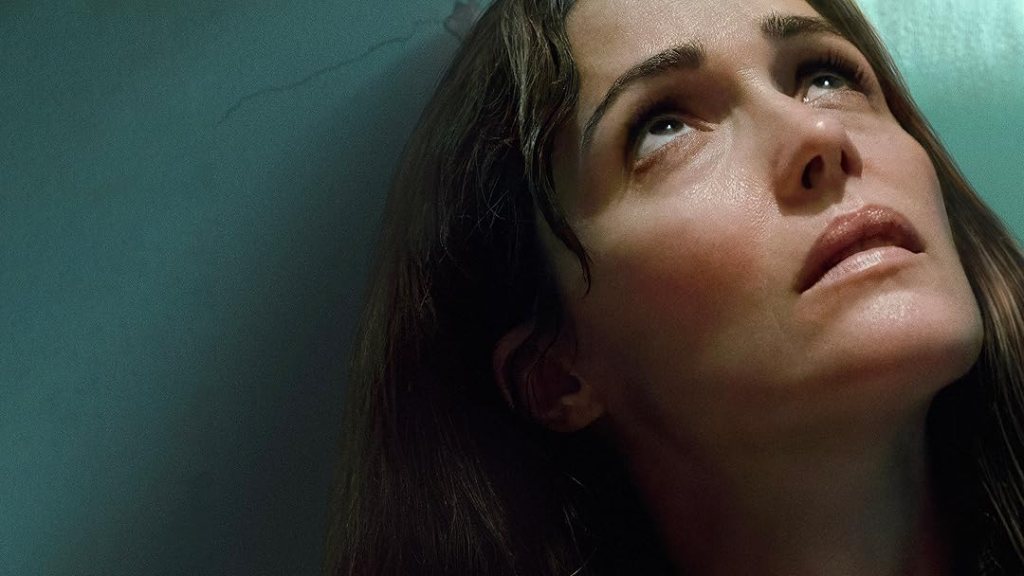

Any alarms going off yet? They should, because possession is quite an intrusion, and its clear the dead woman kept many dark secrets. And yet, neither person leaves. They invite the nightly visits to continue, rolling with the revelation of life after death as if it was expected. That we go along with it is largely due to how well Mongomery and Krieps play these early scenes. They underplay all of it, getting neither excited nor alarmed. They mostly appear weighed down, as if they’re plodding through something that must be done. This synchronism binds them early, well before the plot reveals the depth of their overlap. Only when that unravels does the oddness turn to fear.

The woman has not returned for benevolent reasons, and their possessions quickly begin to torment them. The two are no longer bound by grief but by control. The woman has an unhealthy hold on both of them, and she refuses to let go. It’s a metaphor, of course, one that acutely captures the lingering hold of abusive relationships.

When precisely the audience will pick up on this dynamic will vary, as director/co-writer Samuel Van Grinsven peppers in alarming details throughout the film. When you get it, though, the fact doesn’t derail the tension. Krieps and Montgomery never give their characters a big moment of realization. Instead they crescendo over and over, slightly escalating each time they are pushed towards the truth. The film is methodical, for better and worse. The better is that steady build, which allows the film to be understood at the audiences’ pace. The worse is the lack of infrastructure underneath its ideas. The film is smart, but its intellectualism overshadows its mood.

Despite how much Krieps and Montgomery bring to their characters, they can’t bring in the environment around them. That’s Van Grinsven’s job, and while he clearly had ideas about how its setting would veil the story in oppressive intrigue, the execution isn’t there.

While Jack and Jill are up that hill they are isolated by the impossing terrain, stuck inside an old house designed by the dead woman. They are quite literally stuck in her plans, and that should make the film unbearably oppressive. But the home isn’t shot with precision and the outdoors are often forgotten in the frame’s too-narrow focus. This leaves the film feeling bland, its style only coming out in a few striking shots.

The lack of atmosphere threatens to grind the slowly paced film to a halt. At times, it very nearly does so. The two characters are in no hurry to get past these events, but Krieps and Montogomery’s excellent performances make the plodding into an affecting dirge.

Release: In theaters now

Director: Samuel Van Grinsven

Writers: Samuel Van Grinsven, Jory Anast

Cast: Dacre Montgomery, Vicky Krieps

Leave a comment