Maria Callas. When that name is said, how many of you can picture the renowned opera singer? Or does the name only rings a faint bell, leaving you unable to recall why you know it? Or does it mean nothing to you? There’s no shame in any of the three reactions. One doesn’t need to know the most famous people on the planet, and Callas isn’t high up on that list. Opera is not a popular medium, so it takes an extraordinary talent to break from that stage into mainstream fame. Callas did that, as much as an opera singer can, which speaks to her skill and a certain mythos that makes greats into legends.

Mythos, it seems, is precisely what draws director Pablo Larraín to his female subjects. Maria is the third film he’s made about infamous, tragic women, the preceding films being Jackie (about Jacqueline Kennedy) and Spencer (about Diana, Princess of Wales). In his versions of their lives, all three wrestle with the fame they wield, finding it ungainly and inadequate in the face of real life.

But everyone knows Jacqueline and Diana. The images associated with them are etched into Western culture in a way Callas did not achieve. She was famous like them, of course. And she was tragic like them. But the former duo exists in rarified pop culture ubiquity. Callas was a great opera singer.

This makes her an odd subject to finish out the trilogy, especially as Larraín applies the same dreamy approach as he did in his previous films. In each film, the events take place over a brief period of time. In Maria, it’s the end of Callas’ life. She wanders, dreamlike, through her final days and through her memories. There’s a tangible reason for the film’s disregard of reality; She’s addicted to mandrax (similar to quaalude), and exists in a stupor. To explore her background with the audience, a heavy-handed conceit is built into the plot: the drug causes her to imagine a reporter played by Kodi Smit-McPhee, who questions her about her life. This unravels memories of her mother’s cruelty, her tumultuous relationship with Aristotle Onassis, and her short but astounding career as an opera singer.

It’s all a bit too dreamy, though, especially when wisps of events pass by that you have no context for. Are we expected to know about the performances (or cancellations) that are so frequently referenced? We shouldn’t have to. The film should weave these into observations about Callas, but too often their meaning is light and repetitive.

What is clear throughout is that Callas clings to her art and fame to give life meaning, and this tragic endeavor goes largely unobserved. This is where Maria differs drastically from Jackie and Spencer. Throughout both of those films, the subjects deal consciously with the pitfalls of fame, going so far as to lean into horror in the latter. Callas has no such clarity about her situation. She’s unable to face the harm it is raining down on her despite so many kind people warning her. She’s at the end of her life, and she is simply done. So the film becomes a plod towards tragedy, with little fight from anyone involved.

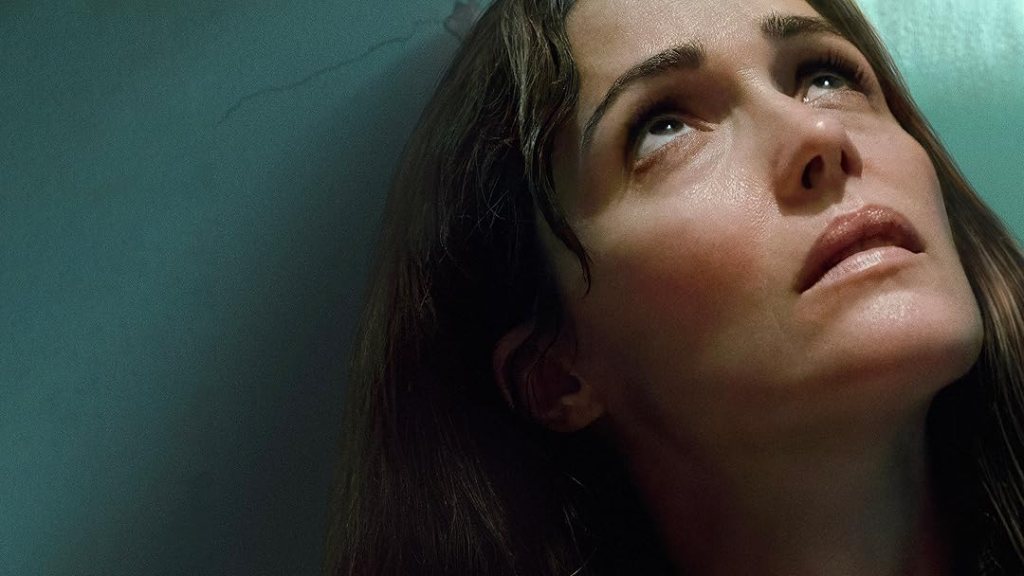

Instead of a strong narrative, Larraín leans heavily on an overbearing style to sustain the film. Much about Callas is conveyed through posturing, both from the particular performance by Angelina Jolie and the lush sets she’s placed in. Everything looks very beautiful but incredibly postured. Callas remains on a pedestal, never coming down to the level of humanity. The effect is distancing, and it makes the film feel like a gorgeous, cold shell.

Jolie does try to find Callas among the artifice, and she nearly succeeds in the film’s middle portion. This is when Callas falls for Onassis, a man who’s too busy pursuing everything life has to offer to adequately love her. It’s also when her relationship with her butler, Ferruccio, and housemaid, Bruna, blossoms. These are the people who most understand her as a person, not the ideal the rest of the film pushes, and it’s through them Jolie is able to find true moments to play.

These interludes almost pull Maria out of the doldrums of a self-important biopic, but always Larraín veers back into overstatement. This is a tiresome film, not because its subject isn’t compelling, but because it never actually finds its subject. Callas is lost in its moody haze. An adored figure, for sure, but a figure. Never a person.

Release: Available now in select theaters. Streaming on Netflix December 11th.

Director: Pablo Larraín

Writers: Steven Knight

Cast: Angelina Jolie, Pierfrancesco Favino, Alba Rohrwacher, Haluk Bilginer, Kodi Smit-McPhee

Leave a comment