Can the child within my heart rise above?

Can I sail through the changin’ ocean tides?

Can I handle the seasons of my life?

In the strange way art interacts and bashes against each other, I found myself humming Fleetwood Mac’s Landslide after watching His Three Daughters. I was quite rattled by the movie, and its aftereffects were difficult to shake. To process, my brain wallowed in a song that felt of a piece; a song about uncertainty, change, and the inevitability of something happening, whether we’re ready or not.

The inevitability the titular daughters face is the death of their father. They’re not ready, as none of us are. Despite it being one of the fundamental aspects of life, the death of someone close to us feels unreal, and there’s no way to prepare for it.

The opening monologue by Carrie Coon’s Katie gets at the helplessness. She’s a pragmatic person. She outlines their goal (letting their dad pass peacefully), demands that this be handled without hysterics, and reveals just how terrified she is in her desperation for control. It’s a fallacy many people fall into, the idea that death can be managed, done right. As Philip Seymour Hoffman screams in The Savages:

People are dying, Wendy! Right inside that beautiful building right now, it’s a fucking horror show! And all this wellness propaganda and the landscaping, it’s just there to obscure the miserable fact that people die! And death is gaseous and gruesome and it’s filled with shit and piss and rotten stink!

There I go again. Art bashing against each other in my head, flitting from one to another, snippets of expression that help me make sense of a whole that’s unintelligible. Much of film criticism elevates the perfect whole, but there’s equal value in a perfect moment. They soothe the soul just as well.

His Three Daughters is an imperfect film filled with perfect moments. You may dislike its performative stiffness, but this gets at the unreality of the experience. You may feel restless within the confines of the New York apartment the daughters are stuck in, but it captures the situation’s inescapability. And you’ll probably want all three girls to just say what desperately needs said, but we all live with unspoken truths.

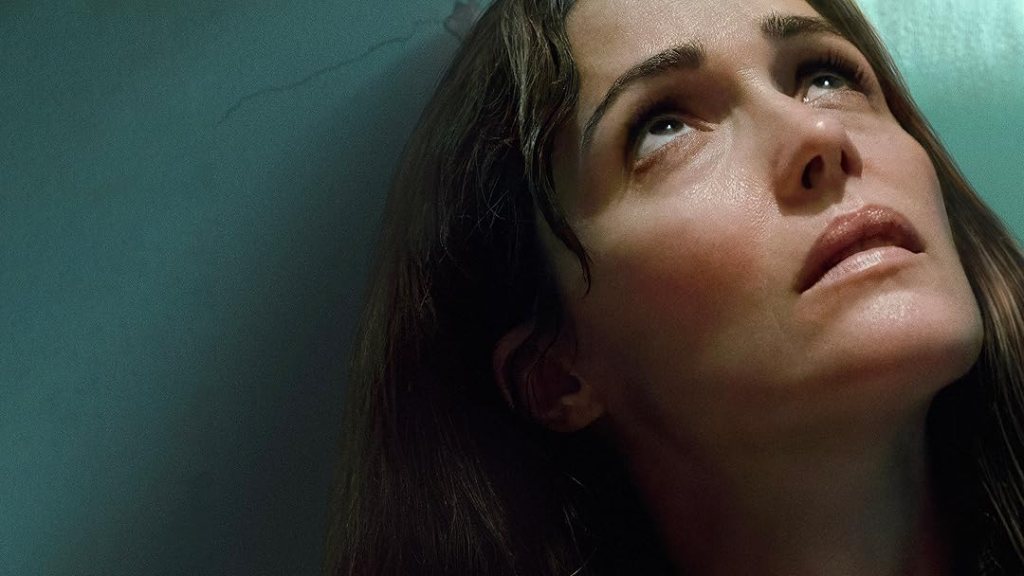

From these formal rigidities come moments that ache with intimate reality. When Natasha Lyonne’s Rachel breaks down thinking about her father and calls him ‘daddy’, she slips into pure emotional memory. The word brings her back to childhood and makes the man dying in the other room into the person she relies on with pure trust. In their real relationship, such rose-colored glasses have been off for a long time. Lyonne is playing a very Natasha Lyonne character: a brash, BSing New Yorker who isn’t going to be pushed around by anyone. Except by her sisters. Except by loss. Except by everything in that apartment that’s making her cling to the man she once believed could take care of everything.

Intimate moments like that abound in His Three Daughters because it captures how all three girls revert to their family roles. They become children again. Their mothers are long gone, and once their father is gone, will they ever be children again? Will they ever fall into the familiar unpleasantness of these roles with each other at their sides?

Rounding out the trio is the MCU-laden Elizabeth Olsen. I don’t bring up her franchise work to disparage her. She’s wrestled one of the most interesting and woefully written characters in that universe into something of note. People who only know her from that massive role may have missed the smaller ones where she’s proven herself a jarring, surprising actress. She taps into the latter skill here, portraying the youngest sister as one constantly caught outside what’s going on with the other two. She’s lonely, frantically so, and neither of her sisters notice. There are times this comes across too broad, a bit trite, but there are others when her fumbling attempts at connection break your heart.

Imperfection is the name of the game here. The film is imperfect. The sisters are imperfect. Their imperfection stems from the rotten roots that bind them. Will they be strong enough to hold? That fear makes them flail like children, desperate not to end up alone.

But they’re older. “Time makes you bolder,” as Stevie Nicks’ croons. They aren’t ready to find the answer, but they must figure out how. If they can get past their childhood roles, there’s a chance the change will leave them more connected. They’ll still lose their father, and that’s a devastating, irreconcilable loss. But they may gain a true sisterhood. So goes life.

Release: Available now on Netflix

Director: Azazel Jacobs

Writers: Azazel Jacobs

Cast: Carrie Coon, Natasha Lyonne, Elizabeth Olsen

Leave a comment