Movies don’t have to be complicated. They don’t need a twist. They don’t have to surprise you. Sometimes a movie finds a vibe it can sustain for 90 minutes and settles right in, being firmly, obstinately, exactly what it is.

That’s the simplicity Immaculate finds. It rightly points out that religious fervor can be terrifying, and it forces you to sit in that fear for its entire runtime.

The film takes place almost entirely within the confines of an Italian convent. Older nuns come there to spend their dying days while the younger serve God through palliative care. Into this demanding world comes Cecilia (Sydney Sweeney), who’s been recruited from America. She’s overwhelmed by the decorous reverie of Italian Catholicism, which only exists in a lesser form in America. But she’s also ready for the convent’s demands, to tenderly care for the women who’ve come before her, and to prove Father Sal’s recruitment of her was warranted. Of course, there’s more to the convent than meets the eye, and Cecilia’s survival comes to depend on how fast she unravels its secrets.

The setup of this chamber piece is a clunky endeavor, with the main characters going through a series of unnatural info-dumping about their history. How convenient that Sister Mary (Simona Tabasco), a fellow newbie at the convent, walks in on Cecilia as she’s using the bathroom. And to smoke a cigarette, because she’s the bad girl of the convent, a little too streetwise for her own good. And of course Sal and Cecilia have a heart-to-heart on the night of her vows, one where she admits her faith is rooted in a near-death experience, as if the man who recruited her wouldn’t know this history.

The rough start quickly smooths out, though, as the crux of the movie hits with perfunctory swiftness: Cecilia is with child, and she hasn’t had sexual relations. An immaculate conception. To nonbelievers, it’s an impossibility. To the Christain faithful, it’s the backbone of their beliefs. All the rigorous decorum on lush display in Immaculate is because Christ was conceived without sin, and another immaculate conception can only mean one thing: his return.

For the faithful, it’s an event to rejoice in. For everyone else, well…the biblical end of the world won’t be very gentle. Cecilia must come to terms with her unexpectedly apocalyptic role, and she must do it alone.

Isolation is a part of all existential considerations. We must die and face whatever (if anything) comes next alone. Cecilia believes in this isolation enough to dedicate her life to the one thing that might greet her on the other side, God, and while His plan for her is unexpected, her faith never wavers. This lends a pointed air to Immaculate. It’s a very Catholic form of horror, but it never takes Catholicism to task. Instead, it frames the horrors of religious fervor as a human creation, and hence taps into an even deeper sense of dread.

What is worse than having the things you believe in turned against you? That’s the reality Cecilia faces, a revelation that is an inevitability, not a twist. If you figure out what’s going on in Immaculate early on, it doesn’t really matter. At its heart are horrors that have gone on for centuries, maybe millennia. Exploited, dehumanized women. Religion wielded without care for the faithful. Damage. Deep, unjustifiable damage that threatens to overwhelm the world, all in the name of God.

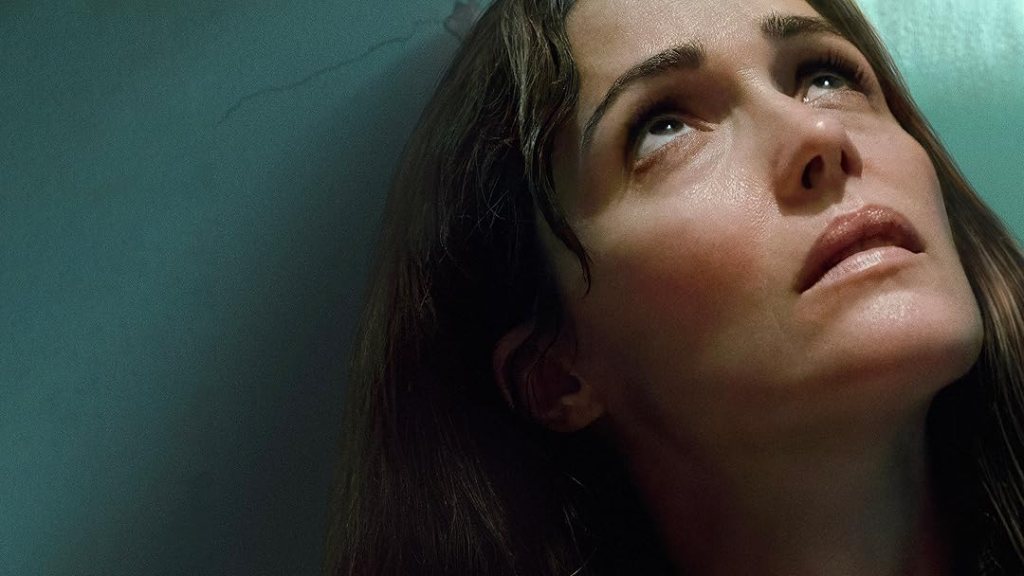

All of this plays out as slow-burn horror, with Sweeney giving an immaculately measured performance. Giving in too early to the danger of the situation would’ve put her faith in question. Instead, she lets the reality slowly creep into Cecilia, making her final, excruciating act a test of her faith in God.

The rest of the movie doesn’t quite meet her extraordinary reserve. A few too many cheap jump scares betray insecurities about the film’s rigorous focus, as if religious dread can’t stand on its own in 2024 America.

It can, and it does, even if the film’s straightforwardness means it won’t terrify you every moment of its runtime. This is more of a chilly meditation on religion. Not a rebuke or a condemnation. Just a warning against going too far and meddling in other’s lives. A timely reminder, if not the most shocking.

Release: Available now in theaters

Director: Michael Mohan

Writers: Andrew Lobel

Cast: Sydney Sweeney, Álvaro Morte, Simona Tabasco, Benedetta Porcaroli, Giorgio Colangeli, Dora Romano

Leave a comment