When Robert De Niro’s William King Hale first appears in Killers of the Flower Moon there’s no mistaking who he is. He’s smarmy, in control, and on auto-pilot. The nonchalance with which he lays out his dirty business would betray how little he has to fear, except he’s not hiding that, either. The only reason he lingers is to ensure his nephew, the perpetually befuddled Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), understands his instructions. Once Ernest’s part of the plan is in motion, Hale is off. No need to babysit something that can go wrong a hundred different ways and not blow up in his face.

Martin Scorsese has brought us plenty of bad men like Hale and Burkhart in his legendary career, but their introductions in Killers make their differences painfully clear. These will not be beguiling men. They will not fall from grace. There is no grace to begin with.

This brusque honesty is the best step forward Killers represents as it inevitably and consciously falls into thorny issues of Indigenous representation in American media. Hale and Burkhart were key figures in the widespread murder of the Osage people after oil was discovered on their land. If white men could get the right paperwork in place (including marriage certificates), all that oil money passed to them upon an Osage person’s death.

It’s a true atrocity, one where Indigenous people were systemically harmed, and one that has been buried by a whitewashed history. Scorsese knowingly chose not to tell this story from the perspective of any of the Osage people involved. Within those limitations, he does a lot right.

The clarity about Hale is spot on, fitting nicely into his long history of humanizing terrible men without ignoring their rot. It’s an important lesson, that monsters are just men, no more terrible or powerful than anything that walks the Earth.

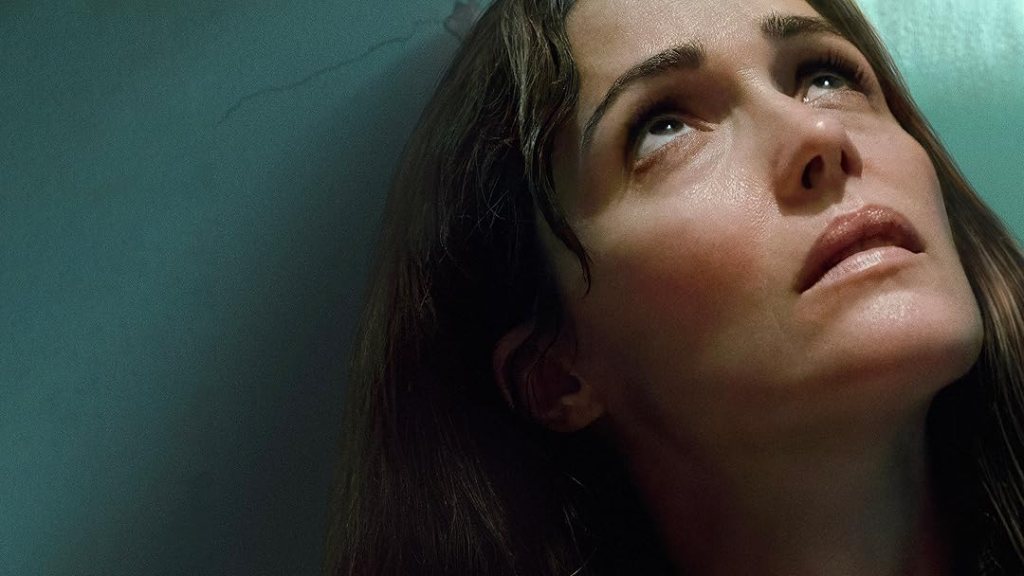

His approach to Burkhart, though, will be divisive. In real life and in this movie, he married an Osage woman named Mollie (Lily Gladstone), was involved in the planning and murder of many of her family members, and began the methodical process of killing her before an early iteration of the FBI put an end to the plot. The bestselling book of the same name on which Killers is based spends more time on Mollie, the Osage people’s circumstances, and the FBI team’s investigation than the movie version does. In fact, this is a very loose adaptation, because somewhere in pre-production the film’s focus shifted from the FBI’s investigation to the marriage between Ernest and Mollie. It’s portrayed as a complicated but loving marriage. This last bit will be a sticking point for many.

I cannot speak to whether it’s possible to love someone and slowly murder their family. What I can speak to is looking someone dead in the eye, someone who should’ve loved me, and explaining the undeniable harm they’d done. I got back genuine bewilderment. I haven’t felt loved by that person since, and I don’t believe they ever loved me in a meaningful way.

A similar scene plays out in Killers, and while that moment feels honest to Mollie’s experience, the circumstances mean Scorsese and DiCaprio had a lot of work to do to convince me of Ernest’s love. In this, the film came nowhere close to success, despite dedicating most of the movie to him. After all, the movie is about Ernest. He is the main character. Watching all three and a half hours of Killers is being stuck with this oafish, shallow, greedy man. Without the complication of the intended love story, he’s just boring.

Partially, this seems intentional. There’s a commentary here about the banality of men like Burkhart and Hale. Their rapaciousness does not make them smart. Their cruelty does not make them terrifying. The grandiosity Scorcese applies is strictly for scale, a clear implication that it’s common white people who took part in and propped up the atrocities. When the movie is expanded out to include a perfunctory investigation by the FBI and a metatextual recreation of how the story was told within white American culture, the implication of white American society as a whole is clear. Not just of these murders, but of the events leading up to them and the events that came after, a long history of systemic brutality and erasure that a single movie cannot capture, correct, or adequately apologize for.

As I said, Scorsese does about as well as he can within his limitations. Most of this is a step forward for how white Americans tell stories about our destruction of Indigenous cultures. However, broader context implicates this story in the continued destruction.

American television has had a small uptick in Indigenous storytelling in recent years. Reservation Dogs, Rutherford Falls, and Dark Winds have made a point to tell stories of Indigenous people with Indigenous people involved in every aspect of the shows’ productions. They’re rare opportunities for a bevy of Indigenous storytellers to get respected credits and build their careers, making this a pivotal moment in American culture. Will they be allowed to continue their careers or will opportunities dry up, the heavy boot of white American culture pushing them down again?

White America has long understood the power of storytelling. That’s why Indigenous people rarely get to tell their own stories, and why stories about them are often told from a white person’s perspective. They’ve been suppressed in ways both overt and covert, and that’s made it easy within white America to prop up the pervasive, harmful system. For the boot to not come down again, we all have to oppose this system.

And that system includes Martin Scorsese scooping up the rights to a bestselling book and taking $200 million to tell the story of white men who murdered members of the Osage Nation. And it includes the fervent defense of his right to do so.

What could have been done with the rights to this book in the hands of an Indigenous person? Disregard what story they might have told with it; Scorsese strayed far afield of the book’s plot. The name of a bestselling book has selling power. $200 million dollars is no small chunk of change, and it’s arguably an unnecessary amount of money for any movie, even if we have become inured to such high budget numbers. And the release of a Martin Scorsese film will generate more words from critics and writers than all those shows, no matter how wonderful they are, ever will.

What hangs over Killers, fundamentally, is a question of space. Scorsese has pointedly given us an epic about white America’s mundane and pervasive cruelty, but is that ultimately helpful or harmful given the cultural moment we’re in? To put it another way: when so many Indigenous storytellers have a firm foot in the door, do we need so many resources to go to another story with white men at its center and the Indigenous people they harmed at the periphery when that perspective is a well-documented part of the harm, including documentation by Killers?

Little writing about Killers meaningfully engages with this question. It rightly praises the message Scorsese set out to make and oblivously ignores the question the film comes right to the edge of asking. It ignores that it is a minor step forward at a moment when major steps could be taken.

Obliviousness, though, is a key factor in the continuation of harm. Scorsese put this observation into Killers, even while obliviously taking up a harmful amount of space. I don’t think Scorsese meant any harm. I think he took great care and had the best intentions with this story. But that doesn’t mean harm wasn’t done. And that doesn’t lessen the contradictions between the film’s messaging and what it does.

Release: available now in theaters

Director: Martin Scorsese

Writers: Eric Roth, Martin Scorsese

Cast: Leonardo DiCaprio, Lily Gladstone, Robert De Niro, Jesse Plemons, Tantoo Cardinal, Cara Jade Myers