Fermi’s paradox questions why we haven’t found extraterrestrial life despite the high probability of its existence. If you’re like me, then the dilemma is profound. A cursor examination of the cosmos, or even the basics of life on Earth, instills a sense of our insignificance, our floundering in the dark, and the idea that we are all that exists in the vastness can cause an overwhelming sense of emptiness.

The answers to Fermi’s paradox range from the empirical to the theoretical, but few get under the skin like the assertion that it’s the nature of intelligent life to destroy itself. Physicist Enrico Fermi posited his paradox in 1950, a mere five years after fellow physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and his team tested the first nuclear bomb in New Mexico. One can imagine why such an answer would hang in the air. Watching Christopher Nolan’s recreation of the blast, it was the only clear thought I could put together: it is the nature of intelligent life to destroy itself.

Sadly, my thoughts seemed to be going against where Nolan was leading, or at least I was off on my own side path. Oppenheimer proves a strangely small movie for its subject, limited in its imaginings of the man and the moment. Nolan frames Oppenheimer as a wrestling with personal perspective in the midst of global ramifications. The haunting answer to Fermi’s Paradox, and even Robert Oppenheimer’s now infamous quotation, shows how much farther people, scientists, and Oppenenheimer himself pondered.

“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Worlds, plural. Because if his worst fears come true, if the bomb he helped create destroys all life on Earth, who’s to say it stops there? Why couldn’t the elusive extraterrestrials find us long after we’re gone, see the scars we left, and get their own inspiration? Ponder that horror.

Oppenheimer is not intelligent nor imaginative enough to consider anything this expansive, instead settling for a jaunt through familiar film genres. There’s the biopic, yes, as we see Robert grow from a young student to the father of the atomic bomb. There’s the tension-screwing middle section of the bomb’s creation and the bookended and interspersed asides about his relationship with Lewis Strauss, who is easy to peg even without historical knowledge.

This isn’t a fatal flaw. After all, we all know the bang this film builds to, and the satisfaction of a good story lies mostly in how well it’s told. Dependent on what you’re looking for, Oppenheimer may satisfy. It’s richly staged, feeling like a capital M Movie for the entirety of its almost three hour length. Stars in the sky and from all levels of Hollywood parade across big sets and immaculately crafted visual effects. A lush score evokes movies of yore, as does the crack of its dialogue. This is Christopher Nolan, after all. The man doesn’t need to prove he can make a Film.

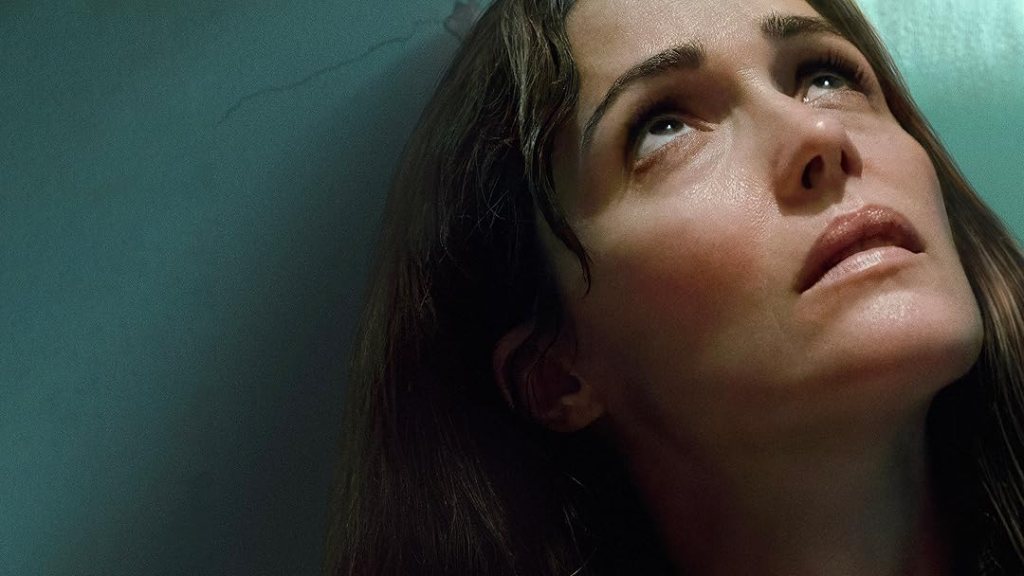

Like so many of his movies, though, the personal remains unexamined. Oppenheimer would have you think it’s digging deep. It postures intelligence precisely but in the end has little to say. Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer never unwinds enough to feel like a complete human being, and the film restricts the moral tussle in front of all these characters so a perfunctory “revelation” can be made in the end.

The film, simply put, suffers from bloat. Long stretches, even while impressive in their construction, get mired in self-important circles. Characters whip in and out without enough time to establish who they are. It must be noted that there’s few women here, and none are given time to build into anything other than clichés. In fairness, most of the men fare little better, but the lack of time given to Emily Blunt’s Kitty Oppenheimer and Florence Pugh’s Jean Tatlock suck dry pivotal scenes.

Oppenheimer would like to be an epic, and Nolan found the right story and assembled many of the pieces to make one. That makes it hard to dismiss the film out of hand, but there’s a lack of imagination, of inquisitiveness, that ultimately holds it back. This is a story about pressing into the unknown and finding a terrible chasm of possibility on the other side. Science does this sometimes. Art does it as well. Nolan has attempted to make an artistic rendering of a scientist standing at a chasm, but his view was so limited that the chasm is barely a crack in the floor. It could easily be leaped without all this pomp and circumstance, and it certainly doesn’t need nearly three hours to wind up.

Release: in theaters July 21st

Director: Christopher Nolan

Writers: Christopher Nolan

Cast: Cillian Murphy, Robert Downey Jr., Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Florence Pugh

Leave a comment